St Mary’s historic wartime fresco is centrepiece to our heritage project for learning, conservation and wellbeing.

Project Rutherford centres on the preservation and conservation of Rosemary Rutherford’s special mural in the Norman round tower, St Mary’s unique 20th century fresco. Its protection within the tower and its promotion involved replacement of the spire shingles, repair of the spire’s wooden framework, repointing of the round tower, conservation of the fresco itself and outreach to all church users and to the wider community in bringing the fresco, and Rosemary Rutherford, ‘out into the open’.

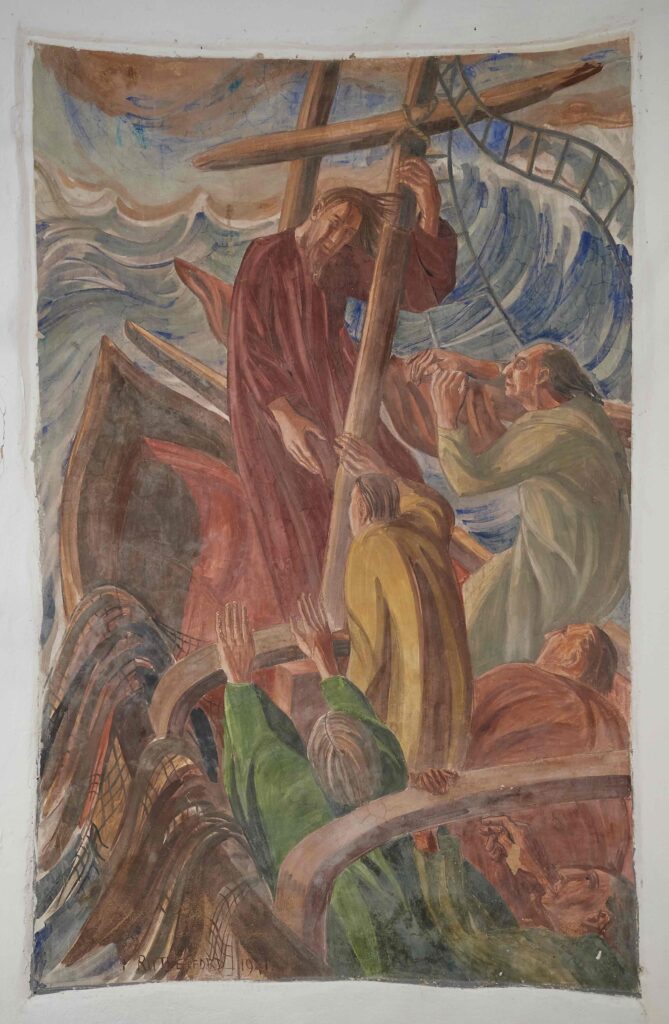

The 1941 Rutherford fresco in St Mary’s tower (Christopher Parkinson)

Rosemary was deeply religious and her spirituality guided her artworks. The fresco painting shows ‘Christ Stilling the Storm’ – she was surely giving people hope during the frightening turmoil of wartime.

On leave from war service in 1941 Rosemary, with the help of her brother Alton, created the fresco in the tower. Rosemary had studied the art of fresco – mural painting onto wet plaster – in the late 1930s. She was keen to put her learning into practice and her father said she could paint on the wall inside the tower. Rosemary and her brother chipped the old plaster off the wall. After dark, Alton would carry away buckets of rubble to bury in the churchyard!

This is one of the very few examples of fresco painting in any English Church.

Rosemary used the complex methods of the old masters – the buon fresco or true fresco technique.

“Each day we laid only as much as could be painted while it was still wet. The colours then sank in and would not peel off.” Alton Rutherford.

She and her brother built up four layers of lime mortar on the cobble wall. The thin top coat was made bright with powdered white marble.

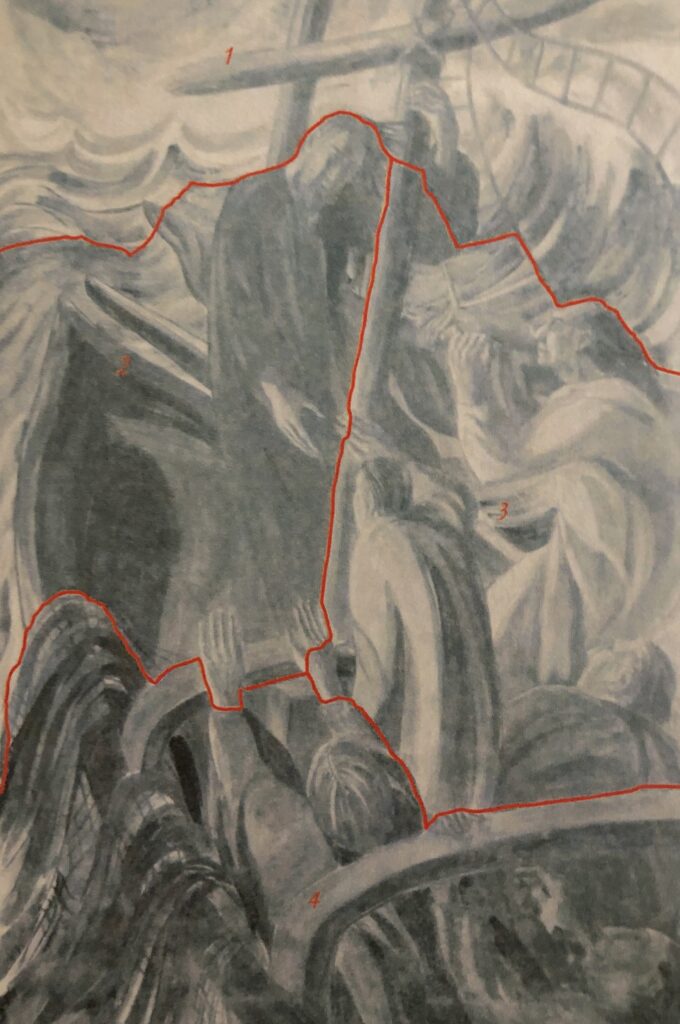

(Tobit Curteis Associates)

Rosemary made a full size ‘cartoon’ from her original sketch. She transferred the picture by incising lines through the cartoon onto the wet plaster. The St Mary’s fresco was painted with her characteristic strong flowing strokes. The colours became permanently ‘set’ within the top layer of plaster.

The fresco was painted in four areas, each enough for a day’s work.

Early in 1943, during an enemy raid across the village, a bomb fell in the churchyard, damaging the church and tower and destroying the windows.

The bishop came to see the damage

– and he saw the ‘secret fresco’!

He turned to the vicar:

“This is new and interesting”, he said.

“But have you got a faculty (church permission) for it?”

“Hitler didn’t get a faculty before he did this lot!”

the vicar replied.

The faculty was granted.

Conservation of the fresco

The fresco in St Mary’s church tower is of considerable significance. It is distinguished by its high technical quality, given that the technique used has rarely proved successful elsewhere in English churches; moreover, it is a very fine example of wartime and post-war experimental art. A 2020 report states that whilst the fresco is in good condition, there is evidence of damage from moisture due to the state of the roof and lack of guttering, the condition of the pointing on the tower walls, and repairs were required to the drainage.

Through more than eighty years, the fresco has suffered from a small amount of accidental knocking and pitting, but the greatest danger – past and future – is the reaction to adverse environmental conditions, notably the transfer of salt during water penetration through the tower wall and into the fresco plasterwork and pigment. Here, dissolved salts can crystallise during evaporation of incoming moisture. The minute salt crystals then stress the plaster layers, including the top layer with its pigment content, by spalling or powdering the plaster. Salt deposits can appear as a hazy or spotty efflorescence on the fresco surface.

It is essential, around many buildings and not just around our historic tower, to check water accumulation and seepage through the footings and base of walls. Salts are dissolved in rainwater from walls, roofs and surrounding grounds and pathways. In particular, the salting of pathways in icy weather must certainly be avoided, as the salt can be transferred in solution readily through a wall even from some distance.

Frescos are robust paintings. In Italy, they are seen on outside walls and these withstand sun, wind and rain. However, some long-term moisture transfer through the wall is unavoidable and thus occasional inspection and conservation work over the long term is essential to preserve the fresco structure for as long as possible, and notably to remove salt from within the fresco’s outer layer and surface by careful conservation work. The specialist cleaning in November 2023 by Claudia Fiochetti of Tobit Curteis Associates has given Rosemary’s work a new lease of life and the removal of salt spots, particularly near the base of the picture, has brightened the image for all visitors to enjoy its magnificence. As part of our outreach programme, Claudia gave a wonderfully informative explanation of fresco technique and conservation during a question and answer session.